The value of a touchdown is a phrase used in formulas like this one

PASSER RANKING = (yards + 10*TDs – 45*Ints)/attempts

where the first thing that comes to mind is that the TD is worth 10 yards and the interception is worth 45 yards. But is it? A TD after all, is worth about 7 points, and in The Hidden Game of Football formulation, a turnover is worth 4 points. Therefore, a TD is worth considerably more than a turnover, but the formula values the TD less. How is that?

Well, let me reassure you that in the new passer rating of the Hidden Game of Football, the value of a touchdown is a constant, equal to 6.8 points or 85 yards. The interception of 4 points is usually valued at 45 yards instead of 50, because most interceptions don’t make it back to the line of scrimmage.

The field itself is zero valued at the 25 yard line. That means once you get to the one yard line, you have one yard to go of field and the TD is worth an additional 10 yards of value. That’s where the 10 comes from. It’s not the value of the touchdown, but the additional value of the touchdown not measured on the field itself.

But what does this additional term actually mean?

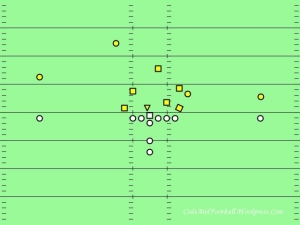

Figure 1. The basic linear scoring model of THGF. TD = 6, linear slope = 0.08 points/yard. The probability of a score goes to 1.0 as the goal line is approached.

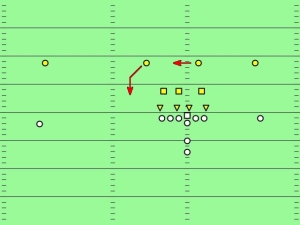

Figure 2. The model of THGF's new passer rating. The difference between y value at 100 yards and TD equals 0.8 points or 10 yards. Maximum probability of a score approaches 75/85.

If you check out the figures above, Figure 1 is introduced in The Hidden Game of Football on page 102, and features in just about all the descriptions of worth up until page 186, where we run into this text. The authors appear to be carving out a new formula from the refactored NFL formula they introduce in their book.

Awarding a 80 yard bonus for a touchdown pass makes no sense either. It’s like treating every TD pass as though it were a 80-yard bomb. Yet, the majority of touchdown passes are from inside the 25 yard line.

It’s not the bonus we’re objecting to-after all, the whole point of throwing a pass is to get the ball into the end zone-but the size of the bonus is way out of kilter. We advocate a 10 yard bonus for each touchdown pass. It’s still higher than the yardage on a lot of TD passes, but it allows for the fact that yardage is a lot harder to get once a team gets inside the opponent’s 25.

and without quite saying so, the authors introduce the model in Figure 2. To note, the value of the touchdown and the yardage value merge in Figure 1, but remain apart in Figure 2. This value, which I’ve called a barrier potential previously, is the product of a chance to score that’s less than a 1.0 probability as you reach the goal line. If your chances maximize at merely 80%, you’ll end up with a model with a barrier potential.

If I have an objection to the quoted argument, it’s that it encourages the whole notion of double counting the touchdown “yardage”. The appropriate way to figure out the slope of any linear scoring model is by counting all scoring at a particular yard line, or within a particular part of the field (red zone scoring, for example, which could be normalized to the 10 yard line). These are scoring models, after all, not touchdown models.

Where did 6.8 come from, instead of 7?

Whereas before I was thinking it was 6 points for the TD and 0.8 points for the extra point, I’m now thinking it came from the same notions that drove the score value of 6.4 for Romer and 6.3 for Burke. It’s 7 points less the value of the runback. I’ve used 6.4 points to derive scoring models for PFR’s aya and the NFL passer rating, but on retrospect, those aren’t appropriate uses. These models tend to zero in value around 25 yards, whereas the Romer model has much higher initial slopes and reaches positive values faster than these linear models.

This value can be calculated, but the formula that results can’t be calculated directly. It can be solved iteratively, though, with a pretty short piece of code

Figure 3. Perl code to solve for slope, effective TD value and y value at 100 yards in linear scoring models.

And the solution is close enough to 6.8 that it’s easy enough to ignore the difference. Plugging 7 points for the touchdown, 20 and 29.1 yards respectively for the barrier potential yields almost no changes in the touchdown value for the PFR aya model and the NFL passer rating formula, and we end up with these scoring model plots.

Figure 6. Amended NFL prf scoring model. TD = 7.05 points, slope = 0.07 points/yard, y at 100 = 5.0 points.