I suspect this whole narrative was kick started by an article in Cowboys Nation that invented something they called the even 4-3. That nothing prior to CN ever talked about a Tom Landry even 4-3 did not stop them, nor did books that mentioned that Tom Landry’s first two defenses were the 4-3 inside and the 4-3 outside. Again, you don’t have to believe me. Read Peter Golenbock’s book on the Dallas Cowboys. We’ll start quoting from page 47 (1).

As a player Landry would not have been presumptive enough to try to formally teach his system to the other defensive players, but as defensive coach, it became his job. He designed a defense he called “the inside 4-3” and “the outside 4-3”.

Going to stop. He didn’t call his defense the even 4-3. The names were 4-3 inside and 4-3 outside.

It was revolutionary because everyone in the past everyone played man-to-man defense. In the past brute strength had been the requisite. You lined up opposite your man, and you tried to beat the crap out of him, using a forearm or your shoulder or a headslap or grabbing him by the jersey and throwing him to one side in an attempt to get by him to make the tackle.

Note that a “gladitorial style” has a lot in common with a modern two gap. It’s a head on collision with the man in front of you.

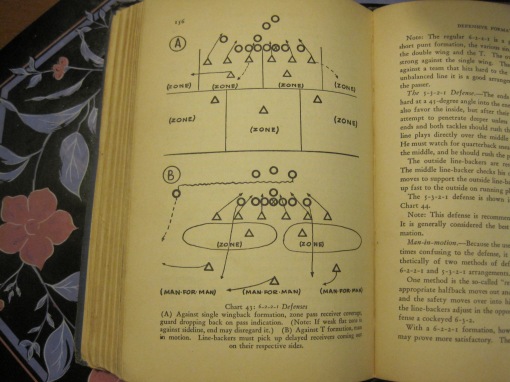

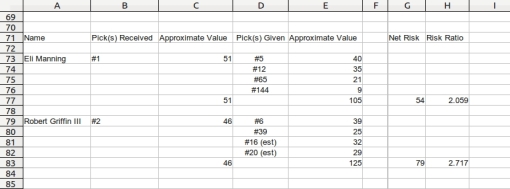

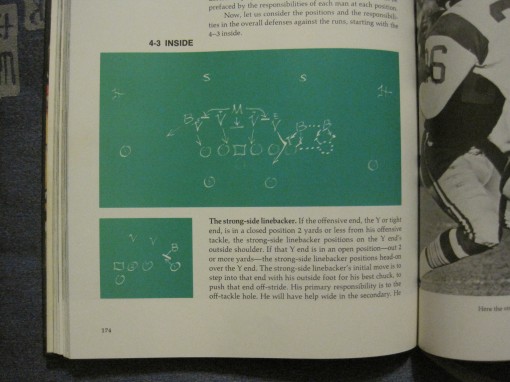

So what were these revolutionary new assignments? Turns out we know because Vince Lombardi took the 43 inside and outside to Green Bay and those defenses he used for the rest of his coaching career. Later, a book called “Vince Lombardi on Football” was written and in that book, every assignment of every player was documented. We’ll borrow some images from my article on the 43 Flex.

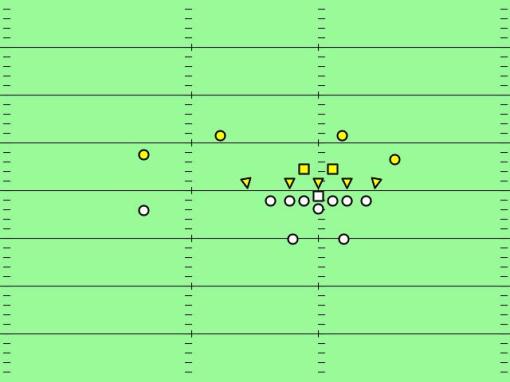

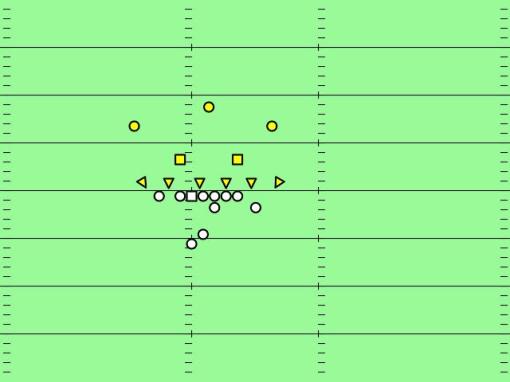

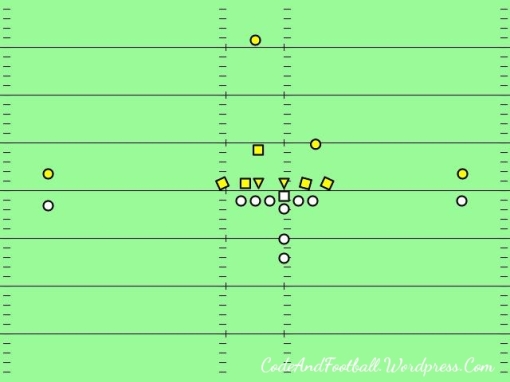

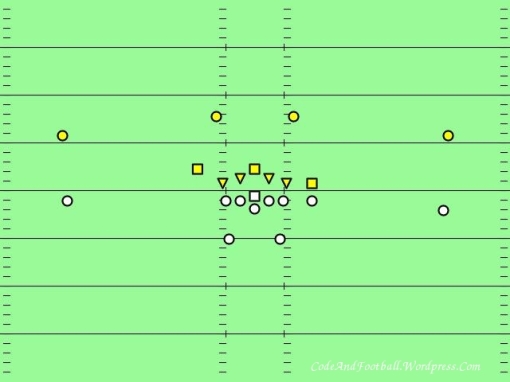

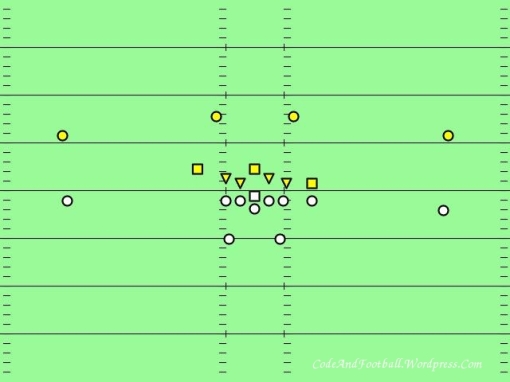

To note, the 4 linemen in the 4-3 inside/outside are not flush on the line. The tackles are flexed, or about three feet behind the line.

Assignments for the line are single gaps. In the inside, the tackles take an A gap and the middle linebacker takes the B gaps. In the outside, the tackles take a B gap and the middle linebacker is responsible for the two A gaps.

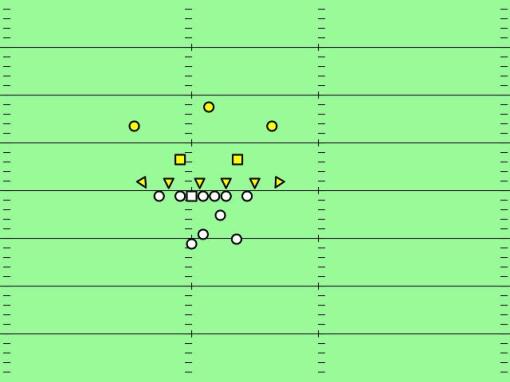

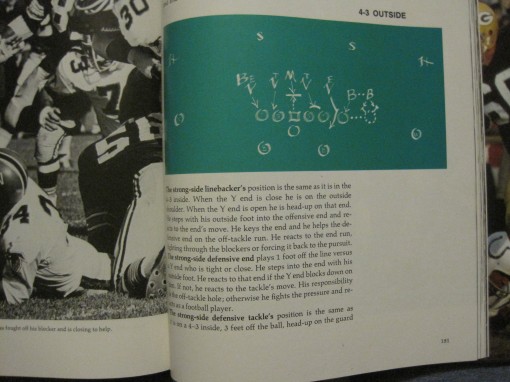

Vince Lombardi on the 4-3 inside

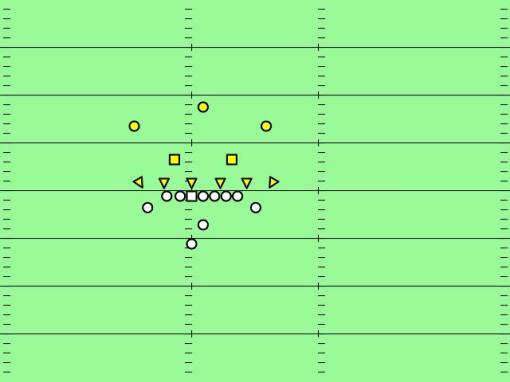

Vince Lombardi on the 4-3 outside

Ok, so maybe his first defenses were one gap defenses. Perhaps the even 4-3 was a change of pace? Perhaps the Flex was a two gap defense? Again, the evidence suggests otherwise. Golenbock, quoting Dick Nolan (2).

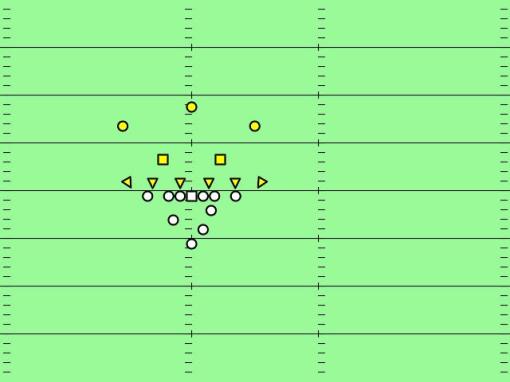

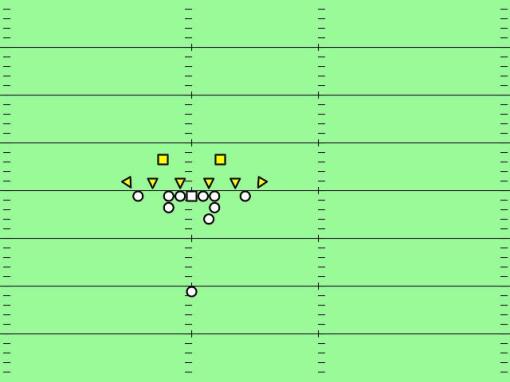

What Tom came up with was the Flex, a combination of the 4-3 inside and the 4-3 outside defenses. On one side you’re playing an inside, and on the other side, you’re playing an outside.

We had been a strictly an inside-outside 4-3 team, like the old Giants, and then in ’64, we used the Flex as a change-up defense…

So, no, Dallas didn’t use a third defense, and neither did the Tom Landry Giants. Those defenses were one gap defenses, and so was the Flex. This can be confirmed by Lee Roy Jordan himself (1).

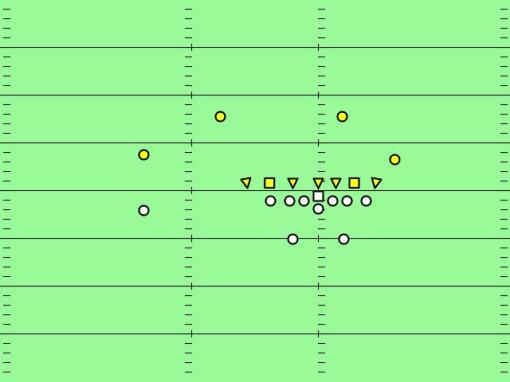

In a nutshell, here is the best layman way I can describe the Flex. There are eight natural gaps on the front line, and in the 4-3 that most teams were using, the four down linemen were asked to control two gaps each. In essence, Coach Landry created a picket fence look, with our right end and left tackle lined up in the conventional spot on the line but the left end and right tackle lined up a few feet off the line, giving them better pursuit angles. The linemen had to control only one gap. The middle linebacker spot now had to control the two gaps on either side of the center. The defense allowed the defensive backs and linebackers to force the play to go where the running backs didn’t want to go. It sure helped me make a lot of tackles during my career. It was a revolutionary defense and created a lot of the motion and spread offenses you see today.

If the description seems confusing, please note that hard core Tom Landry disciples describe the defense “as a QB might see it”, as opposed to the more conventional “as a MLB might see it”. So, in the description above, Bob Lilly or Randy White would have been the left tackle, whereas in conventional notation, they would be considered right tackles.

43 flex. Left to right, front is “4-2-2-5”.

Just to be sure, I got on Facebook and asked Pat Toomay about the notion that Tom used two gap defenses. He replied. To quote Pat:

In a straight inside or outside 4-3, linemen take outside shoulders while MLB has two gap. Not a good run defense, although slanting one way or another was an option for other teams but not for Landry. Hence the Flex. Outside blow-and-go 4-3 was for obvious passing situations. In 3-4 defenses, everybody up front has 2-gap. You need fire-plug linemen for that one. By comparison, Landry’s guys were tall and quick, who were required to take a shoulder rather than go head up, a battle they were unlikely to win, if that makes sense.

In summary, Tom’s defenses were all one gap defenses, where the middle linebacker covered two gaps. As Pat Toomay astutely points out, his linemen were not built to handle a two gap. They were chosen to penetrate and be disruptive. But as Lee Roy Jordan does point out, other defenses of his era did two gap. So the search for the 43 two gap really should extend to other innovative defenders of the era, which would be the Clark Shaughnessy/George Allen Chicago Bears or perhaps the elite defensive teams of the Detroit Lions. I would suggest looking to those teams using 4-3 over and under defensive fronts, as having a tackle over the center lends itself to such a scheme.

Notes

1. Golenbock, p 47

2. Golenbock, p. 233

3. Jordan and Townsend, chapter 10, “The Summer of 1964”.

Bibliography

Flynn, George L (ed), Vince Lombardi On Football, Wallynn Inc, 1973

Golenbock, Peter, Cowboys Have Always Been My Heroes, Warner Books, 1997

Jordan, Lee Roy and Townsend, Steve, Lee Roy: My Story of Faith, Family, and Football, Wood Publishing, 2017 [ebook]